The White Cliffs of Dover are synonymous with England; the stark white cliffs were typically the first and last thing British troops would see when crossing between the battlefields of France and the relative safety of England during the Second World War, becoming a symbol of safety and peace. This has been the case for centuries; being the closest point to France and Europe more generally, the Cliffs of Dover provide a striking welcome to foreign Royalty who were housed at Dover Castle on their journey into England, and a key site of defence when relations are not so cordial. Located just over an hour from London by train, Dover makes for a jam-packed day trip with many places to explore, excellent hiking trails and centuries of history to delve into.

- Geology of the chalk cliffs

- Itinerary:

- Sources

Geology of the chalk cliffs

These stark white cliffs of made of chalk, continuing across into France on the other side of the channel. Formed over 70 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period when England was submerged in a shallow sea, the skeletons of tiny micro-plankton, coccolithophores, built up layer by layer on the sea floor to create a white mud, forming the immense amount of calcium carbonate needed to make the chalk cliffs we see today, compacted and hardened over time. Estimates suggest that half a millimetre was deposited per year, taking an unfathomable length of time to form the 110m high cliffs. The purity of the chalk suggests that this site was far from land, otherwise silts and sand from the land would have contaminated it. Evidence suggests the nearest land was located where Wales is today.

While a shallow sea in the Late Cretaceous, the chalk is now obviously well above sea level, the result of substantially lower sea levels today than during the Late Cretaceous combined with the uplifting from the collision of the European and African continental plates that resulted in the formation of the Alps 25-30 million years ago.

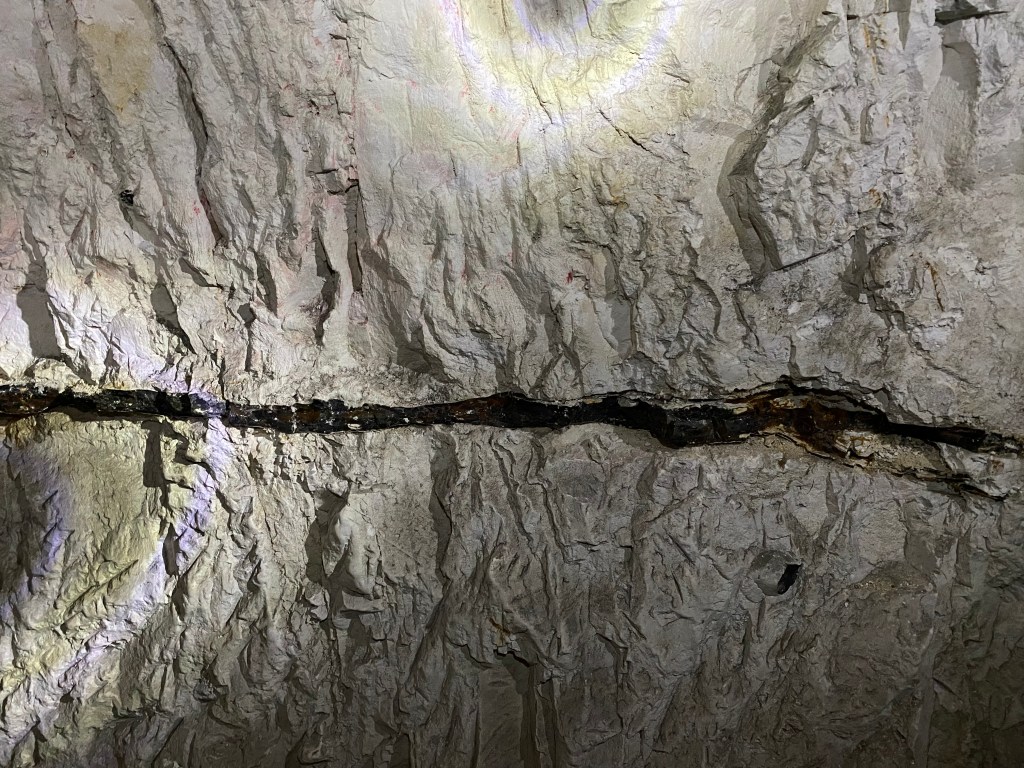

The cliffs are constantly eroding, exposing fresh white chalk. Also noticeable are the horizontal bands of flint running through the cliff face, which have been shown to continue in the same bands well into France. Flint is inorganic, made up of silica, silicon dioxide to be more specific which is found in sand, quartz and flint. The silica comes from the remains of sea sponges and silicon-containing planktonic micro-organisms that are deposited in the sea bed when they die and burrow into the sea floor. Flint is formed within chalk, where silica replaces the calcium carbonate molecule-for-molecule. Chalk (calcium carbonate) is alkaline, so requires an acid for it to be dissolved and silica precipitated (the formation of a solid from a liquid solution following a chemical reaction or change in temperature). Hydrogen sulphide, created through bacterial activity in the sediment of the sea floor, reacts with dissolved oxygen migrating towards the sea floor. This creates an acid which dissolves the calcium carbonate and the silica is precipitated to form flint. Before hardening, it fills any burrows made by marine creatures, hardening into nodules of all sorts of interesting shapes and sizes.

Why this occurs in layers is still a mystery with two possible explanations. The first theory is that the chalk sedimentation occurs in cycles, while the second is that the process described above uses up all of the silica within that depth of sediment, so the process of flint formation can only restart once there is enough silica again.

This flint was crucial in early human history, providing an extremely sharp blade used as arrow-heads for hunting and as a cutting tool for food preparation, among many other uses. Extremely durable as a building material, flint is seen in buildings all throughout the south of England long after it was used as a tool, used by the Romans in their extensive wall and road building, as well as by the local people ever since.

Itinerary

With so much to see and do, I arrived in Dover for 10am. If an early start is not your thing, an overnight stay may be better to ensure you have enough time at each location and to make the most of your time along the cliffs. On a gorgeous sunny day like I had, I would have loved to sit in the deck chairs beneath the lighthouse or in the grass along the cliffs for longer, but had to keep moving to ensure I would have enough time at the castle being my last stop.

White Cliffs of Dover Hike

Key Details:

Setting off from the train station, I headed for my first stop at the National Trust Visitor Centre where my hike would truly begin. If you are driving to Dover, I would recommend parking at the visitor centre and walking from there, otherwise it is 3km and 30mins walk.

From the station, it is a fairly dull walk along pavements beside busy roads filled with cars heading for the channel tunnels or towards the ferry to France, but you soon reach a set of stairs taking you up to the cliff top. From here you get an interesting view over the Port of Dover, watching the constant flow of ships coming in and out. Reaching a stile, it is a relief to get off the pavement and onto the chalk cliffs themselves; much nicer underfoot, you are surrounded by the flora and fauna of the chalk grasslands, with wild flowers and butterflies either side and the shimmering, blue channel to your right.

Reaching the visitor centre in half an hour, I stopped for a quick toilet break and a nosy through the well-stocked gift shop, then carried on for my next stop. The visitor centre has plenty of outdoor picnic tables in the shade, as well as a large undercover seating area and plenty of food and drinks on offer from the cafe. There is also a lovely second-hand book store, which I had to resist entering with every fibre of my being!

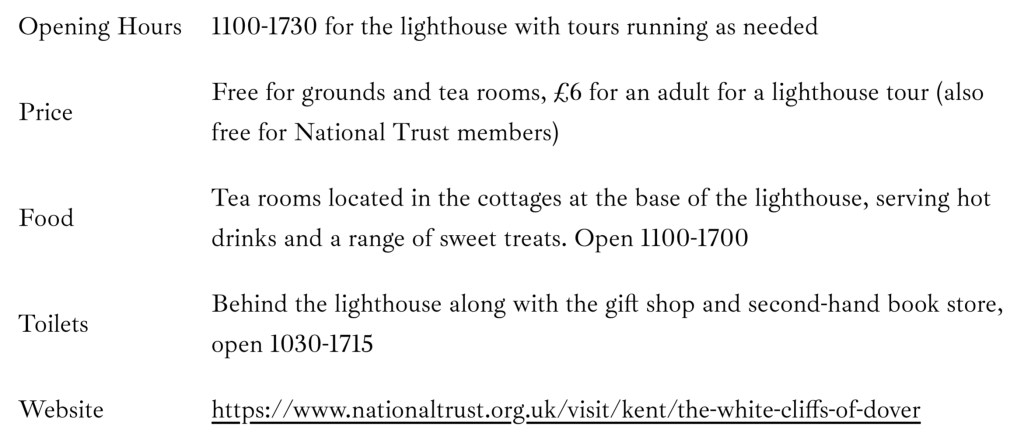

National Trust: White Cliffs of Dover Visitor Centre

Key Details:

From the visitor centre, it is a gorgeous and easy 2km hike along the cliff side to Fan Bay Deep Shelter. This took me just under 30mins as there was so much to photograph, but there is a well-made track to follow, easily visible because of the blindingly white chalk!

There is a large biodiversity on the cliff tops, including the bright pink pyramidal orchid, which flowers between June and July, and the chalk hill blue butterflies. As this area has been subjected to grazing for centuries since the arrival of domesticated animals with humans thousands of years ago and even before that to the wild cattle and ponies at the end of the last Ice Age, the landscape has come to rely on grazing for survival and maintaining biodiversity. The underfoot disturbance of the grazing Exmoor ponies and cattle now in the area create a mosaic effect, with different pockets of plants growing out of the disturbed soil.

Fan Bay Deep Shelter

Key Details:

Fortunately there are signs on the track, as it would be easy to walk straight past the Fan Bay Deep Shelter entrance unless you are looking out for it as it is tucked into the cliff side and the mesmerising views to your right across the channel are very distracting! Along with the signs, there is also a flag pole and seating area covered in camo netting, so if you are looking for it, you should have no trouble finding the entrance.

Arriving at the shelter just before the first tour of the day started at 1100, the tiny group I joined and I were given a safety briefing and donned our hardhats and head torches before descending the 120-odd steps into the gloom of the tunnels. Located deep under the chalk cliff-side, these tunnels were constructed in 100 days at the orders of Winston Churchill in late 1940 to disrupt enemy use of the channel and batteries. He stated in a speech in August 1940 in anger at the lack of defence along the coastline and number of enemy ships in the channel, “we must insist upon maintaining superior artillery positions on the Dover Promontory, no matter what form of attack they are exposed to. We have to fight for command of the Strait by artillery, to destroy the enemy batteries and fortify our own.” This led to a flurry of activity along the coast, resulting in the rapid construction of the tunnels and battery at Fan Bay, as seen today.

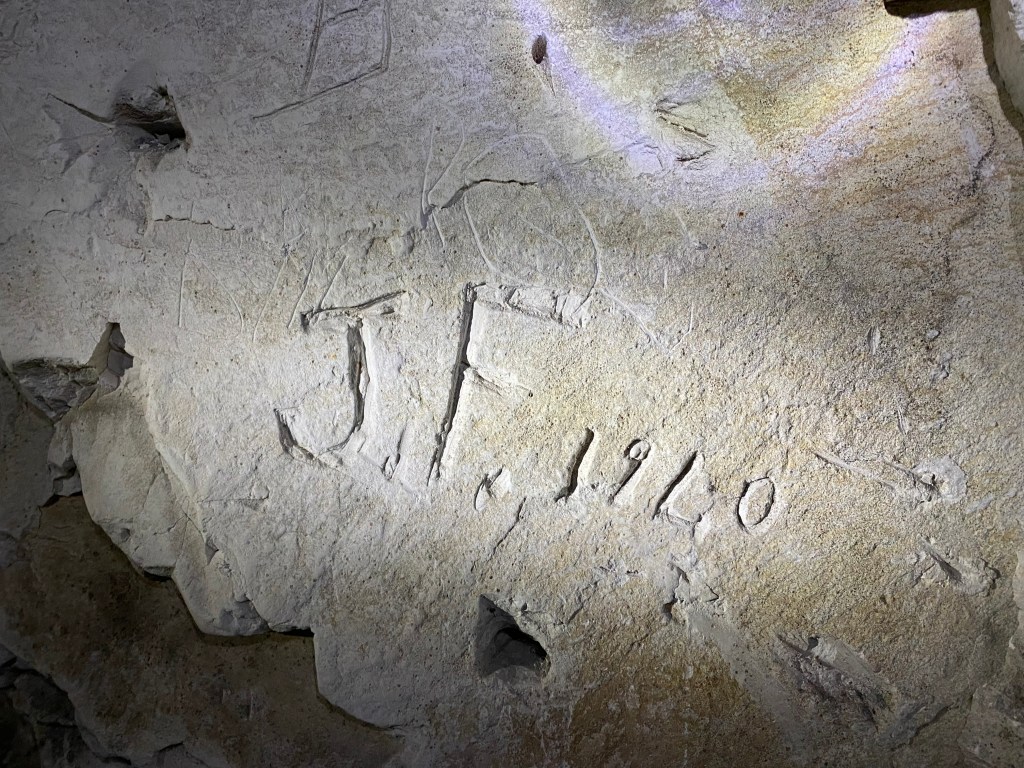

The tunnels were drilled inwards by hand into the chalk cliffs by teams of Royal Engineers and the 172 Tunnelling Company, supported by steel arches and galvanised corrugated iron. These tunnels were to provide accommodation to 154 troops stationed at the battery as well as protection in the event of shelling or bombing, as depicted in the watercolour sketch below. Conditions were pretty damp and smelly, so barracks were eventually built above ground and this was maintained for emergency use instead.

Walking within the chalk cliffs is fascinating, as along with graffiti etched into the walls by the troops during WWII (and some from more recent times), there are fossils of larger creatures within the ceilings, as well as a very distinctive line of flint running through the walls.

Also at this site are the Sound Mirrors. With the invention of airplanes, Britain’s coastline was subject to aerial attack for the first time during WWI. To aid with the detection of enemy aircraft, many Sound Mirrors were constructed along the south coast of England. Constructed from heavy-duty smoothed concrete shaped into a concave dish, the sound from aircraft is concentrated into the centre of the dish and reflected into a listening piece that could be angled to determine the aircraft location. This technology saved countless lives, but was made redundant by the 1930s with the invention of radar and the massive increase in aircraft speeds.

During the 1970s, Operation Eyesore set out to destroy all evidence of war in the towns and so-called “beauty spots” throughout Great Britain, such as the Fan Bay Deep Shelter and batteries along the White Cliffs of Dover. For this reason, all structures above ground were levelled and the debris was used to fill in the tunnels. Unable to destroy the Sound Mirrors due to the strength of the reinforced concrete, these, along with all evidence of the tunnels, were covered in vast quantities of soil and chalk from local areas, compacted by bulldozers, and forgotten about in the following decades with the lack of visible evidence. Once the National Trust gained ownership of the land, excavation works were commenced to restore the tunnels and Sound Mirrors to their former appearance.

Re-emerging into the bright sunlight and warmth after the cool, dark of the tunnels, I continued east along the coastline to my next stop, South Foreland Lighthouse. The wildflowers and a gorgeous white sailing boat made the just over 1km up to the lighthouse disappear with ease.

South Foreland Lighthouse

Key Details:

With fresh paint, brightly-coloured bunting and summer deck chairs on the grass, South Foreland Lighthouse has immediate appeal. For the summer holidays, the National Trust had set up games on the grass and with a tea room, lighthouse tours, gift shop and second-hand bookshop, this spot is well-worth a visit.

I thoroughly enjoyed my packed lunch and a fresh fruit scone with jam and cream from Mrs Knott’s Tea Rooms which is decked out in 1950s decor with bright floral wallpaper and antique furniture. There is plenty of seating inside the tea rooms, what was once the accommodation for the lighthouse keepers and their families, as well as ample picnic tables outdoors. With many sweet treats on offer, it is hard to resist a stop!

Refreshed, I joined a tour of the lighthouse, which run throughout the day as needed between 1100 and 1500, lasting around 45mins. I learnt all about the history of the lighthouse and seeing the rotating clockwork mechanism of the lens in action gave me a deeper appreciation for the work and importance of the lighthouse keepers at this spot in the past. A walk around the top of the lighthouse topped off the tour in every sense, as while it didn’t look particularly high from the ground, the views to the little village of St Margaret’s and across the channel to France were fantastic, particularly with a lovely cool breeze on my face.

The lighthouse was built in 1846, but there have been warning lights on this section of the cliffs since the 14th century to warn against the Goodwin Sands, a hidden stretch of sandbank covering a huge area of the channel from South Foreland to Ramsgate that has claimed many ships and lives throughout time. There are actually two lighthouses; the lighthouse that is open to visitors is the Upper Lighthouse, while the Lower Lighthouse is right at the cliff edge. The idea was that if you could line the Upper directly above the Lower Lighthouse, you knew you were safely clear of the southern end of the Goodwin Sands. As the Sands are constantly moving, by 1904 this arrangement was no longer safe, so the Lower Lighthouse was decommissioned and a much brighter, flashing light was installed at the Upper Lighthouse. Even this lighthouse eventually reached the end of its working life; the introduction of modern navigational technology meant that the Upper Lighthouse was decommissioned in 1988, from which point the National Trust gained ownership of the property.

Located not far to the east of the Fan Bay Deep Shelter, the South Foreland Lighthouse has also been marked by the tumultuous Second World War. To prevent aiding the enemy, the light was completely switched off throughout the war and the tower camouflaged. Even still it suffered some shrapnel damage, visible on the lens today. A radar system was also installed here, allowing shipping to be tracked and guns to be fired at night and when visibility was poor.

South Foreland Lighthouse has also been the site of many modern technological advancements, becoming the ideal location for experiments in Marconi’s new wireless technology in the late 1890s, recording the first ever ship-to-shore radio transmission. It was also the first lighthouse to use an electric light as Michael Faraday, one of the key scientists working with electricity, was Scientific Advisor to Trinity House, the owner of South Foreland Lighthouse (along with most of the lighthouses throughout the UK).

Initially completing the loop as shown in the map above to return to the National Trust Visitor Centre, I started on this route but found it to be along a road so opted to return along the path closest to the cliffs again to make the most of the stunning views.

Reaching the Visitor Centre once more, I set off for Dover Castle on foot. While I made it in one piece, I would definitely only recommend following the route shown on Google Maps; the route that I found probably saved no time and involved some sketchy sections along the side of the road thinking I knew better than Google Maps. I did, however, find myself at the memorial that marks the site Louis Blériot crash-landed the first successful flight across the English Channel, from Calais to Dover in July 1909. Blériot was an early French airplane manufacturer and aviator, using the fortune he made manufacturing headlamps and other car accessories to fund his early aeronautic experiments, building and testing a range of powered aircraft prior to his successful channel crossing. This cemented him as one of the leading aircraft pilots and manufacturers of the time. His factory was responsible for producing a significant proportion of the aircraft used in the airforces of America, France, Britain, Italy, Austria and Russia during WWI and flying clubs across the world purchased his aircraft, dominating competitions for speed, altitude, distance and duration.

Hot and sweaty, I arrived at the Castle ready for an ice cream before exploring.

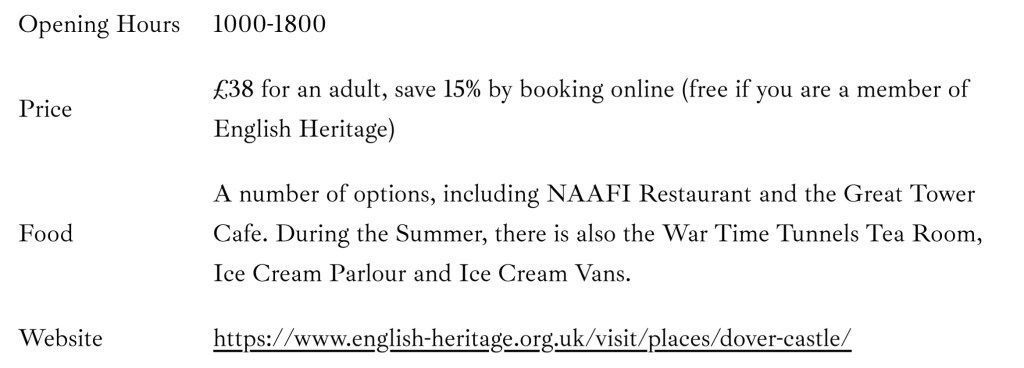

Dover Castle

Key Details:

With its strategic location at the shortest point of the English Channel between France and England, high up on the White Cliffs, Dover Castle has been key to the defence of England’s coastlines since its construction in the 12th century following the Norman conquest. The original settlement at Castle Hill where the Castle stands today may be pre-Roman Iron Age, but certainly from the Roman invasion onwards this location was picked as a site of importance. The Romans constructed a fort at the mouth of the river Dour, which runs through Dover town, along with a lighthouse on Castle Hill and a second on the Western Heights, the opposite hill, providing a navigational aid to find the fort.

The port at Dover was captured by William the Conqueror in 1066 following the Battle of Hastings, building a fortification, but nothing remains of this.

The castle that you see today was built by Henry II in the 1180s. Spending vast sums, the Castle was the most advanced of its time in Europe, made up of an immense Great Tower surrounded by an inner bailey and towers and an outer bailey. The Great Tower was built as a defensive structure, but contained all the luxuries of a Royal Palace.

The Castle was visited by many Royals until the 17th century, with visitors including Anne of Cleves on her way to visit Henry VII in 1539 and in 1573 by Elizabeth I to ensure the castle was in good condition during the war with Spain.

The castle was little used from this point until the 1740s, when Great Britain entered into conflict with France, their rival world power. Barracks were constructed out of the castle which housed around 800 infantrymen and modifications were made to be able to withstand cannon fire. Extensive renovations were made during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, with better earthworks defences to defend against cannon fire as well as for mounting cannons. Underground barracks were also built at the southern end of the castle, vast gunpowder stores were built and a new entrance was created to the south-west. By the end of the war in 1815, Dover Castle was an immense artillery fortress and barracks. This did not last, as following reductions in military expenditure after 1815, the army moved out and the underground barracks (the Casemates) were used by an anti-smuggling force, the Coast Blockade, instead from 1818-28.

By the 1840s, defences were improved again and new barracks built, which can be seen today. Large guns were established along the cliffs here in the 1870s with the ability to fire far out into the Channel to defend against steam-driven warships.

During WWI, Dover Harbour housed the Royal Navy’s Dover Patrol whose responsibility it was to defend the Dover Strait, particularly against German submarines, as well as protecting communications with France and Flanders. The Castle was the headquarters for approximately 16,000 troops and many training camps for troops heading to the Western Front were located here. Airships and airplanes were a threat for the first time, requiring new defences such as anti-aircraft guns (and the Sound Mirrors at Fan Bay Deep Shelter).

WWII gave Dover Castle great importance once more, reinstated as the Royal Navy base and headquarters for the Army garrison defending the town. The underground barracks (the Casemates) were repurposed as bomb-proof offices for the Navy, as well as army units coordinating coast artillery and anti-aircraft defences. These offices were where Operation Dynamo played out, the evacuation of 338,226 British and Allied troops from Dunkirk in 1940, run by Vice-Admiral Ramsay. A layer of tunnels was added above the Casemates, known as the Annexe, where a small hospital was located following its construction in 1942, as well as a lower level called Dumpy which served as a Combined Headquarters (CHQ) where Operation Neptune was planned and run from, the naval side of the D-Day landings, as well as Operation Fortitude South, which successfully deceived the Germans into thinking the main invasion was planned for landings around Calais rather than Normandy.

Vacated by the Army in 1958, it was selected in the 1960s as a Regional Seat of Government to be occupied in the event of a nuclear war. The Dumpy level was to contain the main seat of power. The Casemates and Annexe were to be repurposed as dormitories, dining areas and bathrooms, sealed against contamination and given air filtration and communications equipment as well as a small radio broadcasting studio.

After cooling down with my ice cream, I enjoyed the views from the battlements and headed for the Great Tower. This structure is truly immense, and I was constantly surprised by how many rooms there were inside and how big they were, on top of how lost I felt wandering from room to room across multiple levels, especially considering the relatively simple appearance from the outside. Also in contrast to the simple, unembellished exterior was the lavishness of how it would have appeared in the Medieval period. The views from the top were also fantastic, as you would expect from such a vantage point.

I also did a tour of the Casemates, which takes you through the importance of this site throughout WWII, particularly in Operation Dynamo. Running for around 45 minutes in groups of 30 regularly throughout the day, I found that while interesting, the tour was extremely rushed and did not do justice to the wealth of history located throughout those tunnels and was starkly juxtaposed to the tour of Fan Bay Shelter which is considerably smaller, but much more thorough. Still worth doing, but expect to be power-walking from one room to the next to catch the video and audio presentations, with no time to absorb the atmosphere or take note of details such as the graffitied walls.

Walking back through Dover town to catch a return train in the late afternoon, I was exhausted from information overload, but had had a great day in such an interesting and beautiful place.

Sources

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/kent/the-white-cliffs-of-dover/our-work-at-the-white-cliffs-of-dover

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/kent/the-white-cliffs-of-dover/fan-bay-battery—a-brief-history

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/kent/south-foreland-lighthouse/history-of-south-foreland-lighthouse

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-Bleriot

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/kent/the-white-cliffs-of-dover/the-fan-bay-deep-shelter-project-at-the-white-cliffs-of-dover

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/history-dover/

http://www.discoveringfossils.co.uk/dover-kent/

https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Education-and-Careers/Ask-a-Geologist/Earth-Materials/Flint-Formed-in-Chalk#:~:text=Where%20the%20dissolved%20oxygen%20and,structure%20of%20many%20marine%20organisms.

http://snpr.southdowns.gov.uk/files/additions/For%20how%20flint%20is%20formed.htm

Leave a reply to jameskeneally Cancel reply